Vet Practice Owner Salary: What Clinic Owners Actually Earn

A vet practice owner’s salary is part compensation, part reward for risk, part substitute for profit. It varies depending on whether the owner is producing cases, overseeing a team, prepping for exit, or just trying to stabilize after a tough year.

What most veterinary owners miss is this: salary isn’t just about paying yourself, it’s about positioning yourself. If you’re overly dependent on your clinical production to justify income, you may be limiting the business’s valuation down the line. If you underpay yourself to “leave more in the business,” you may distort profitability and reduce buyer interest.

This blog provides a comprehensive overview, covering clinic revenue benchmarks, production versus profit mechanics, and how savvy owners structure their compensation during growth, reinvestment, and pre-sale phases. Because in this industry, your salary is a signal to buyers, to bankers, and to the business itself about how well your clinic is truly performing.

What Does a Vet Practice Owner Earn Today?

There’s a tendency among veterinary clinic owners to equate their annual income with what shows up in their personal bank account. But the true vet practice owner salary is the net earnings that remain after including staff, inventory, equipment, marketing, and all those unexpected costs that come with ownership.

For solo DVMs handling a full caseload, personal production might exceed $1.3M/year. However, once you back out fixed overheads, variable costs, and payroll, the owner’s real income may look closer to $180K – $250K, with most of it tied to clinical effort, not business performance.

Quick Tip: If 90% of your income is coming from your own hands-on production, you’re not running a business; you’re operating a job with overhead.

Where this dynamic begins to change is in multi-vet practices where the owner reduces clinical hours and focuses more on team output, strategic pricing, and cost control.

Practices with well-managed DVMs and clear margin discipline often support owner incomes in the $300K – $500K+ range because the business runs beyond them.

One common misstep? Owners assume their high production translates to a high sale value, which is a costly mistake during exit. A heavy reliance on owner output often depresses valuation multiples.

Buyers reward transferable infrastructure. This becomes especially clear in corporate acquisition offers, where personal income has little bearing unless tied to scalable operations or margin performance.

Vet Practice Owner Salary vs. Associate Vet Income: What’s the Gap?

The gap between associate pay and vet practice owner salary is often discussed in absolute numbers, not in context.

That’s where confusion starts.

Associates see the gross revenue flowing through the clinic and assume ownership income rises proportionally. In reality, ownership income behaves very differently once overhead, risk, and reinvestment enter the picture.

Consider two professionals working in the same clinic.

- Reality of Associate Vet Income: An associate producing roughly $550K annually is typically compensated through a fixed salary or production split. Their income arrives predictably. There’s no exposure to payroll overruns, no responsibility for inventory miscalculations, and no obligation to fund capital purchases. Once the day ends, income is done for the day.

- Reality of Clinic Owner’s Income: The owner may produce twice that amount personally. But that production supports the entire operation first. Staff costs, lease obligations, lab fees, compliance expenses, and software subscriptions all get paid before owner income is finalized. The result? A higher gross number with far more volatility underneath it.

Key distinction: Associate income is insulated.

Owner income absorbs the shocks.

Where the Gap Actually Emerges

The income gap only begins to widen meaningfully when owner compensation is no longer dependent on personal clinical output. That happens when:

- Multiple DVMs are producing consistently

- Appointment capacity is no longer tied to one schedule

- Pricing discipline is enforced across the clinic

- The owner shifts time toward leadership, not case volume

At this stage, owner income is driven less by hours worked and more by margin discipline. Without that shift, the difference between associate pay and owner pay narrows far more than most expect, especially on a per‑hour basis.

This is also where many owners feel frustration: high responsibility, long weeks, and income that doesn’t feel proportionate. Those pressures are commonly cited in discussions around corporate veterinary ownership problems, particularly when clinics grow without fixing structural inefficiencies first.

How Much Money Does a Vet Clinic Make a Year?

When clinic owners ask how much money a vet clinic makes a year, they’re often searching for a benchmark they can measure themselves against.

The problem is that annual revenue in veterinary practices doesn’t follow a narrow band. Instead, it spreads widely depending on how the clinic is built, staffed, and priced.

Two clinics operating in the same city can report vastly different annual revenue numbers, even with similar caseloads. The reason usually comes down to capacity utilization.

What Annual Revenue Looks Like Across Common Setups

1. Solo‑DVM clinics

These practices often plateau earlier than expected. With one schedule, one treatment flow, and limited appointment flexibility, annual revenue commonly settles between the mid‑six figures and low seven figures. Growth slows because there’s no room left to add volume without extending hours or compromising service quality.

2. Two‑to‑three DVM clinics

This is where revenue acceleration tends to occur. Additional schedules allow overlapping appointments, better use of support staff, and improved case throughput. Clinics at this stage often cross into the multi‑million‑dollar range, but only if pricing, staffing ratios, and scheduling discipline evolve alongside growth.

3. Larger multi‑DVM clinics

At four or more DVMs, revenue potential increases substantially. But so does complexity. Clinics that maintain operational control continue to scale. Clinics that don’t often see revenue flatten despite higher headcount.

| Distinction: Revenue growth without operational alignment often creates stress, not profit. |

Why Revenue Alone Can Be Misleading

Annual revenue answers only one question: how much money flows into the clinic. It doesn’t explain:

- How much of that revenue remains after payroll and inventory

- How dependent is revenue on one individual

- Whether the clinic can maintain performance if staffing changes

This is why many owners with strong top‑line numbers still feel financially constrained. Revenue has increased, but efficiency hasn’t kept pace. That tension shows up clearly when viewed against broader veterinary practice market trends, where rising demand hasn’t translated evenly into owner income.

Vet Income vs Sale Value: What Owners Often Get Wrong

One of the most persistent misunderstandings in ownership is assuming that a strong vet practice owner salary naturally leads to a strong sale outcome. In reality, income and value often move in different directions, sometimes in direct opposition.

Many owners earn well because they personally produce heavily. Their schedules are full, their clinical output is high, and cash flow feels healthy. But when the time comes to evaluate the business as a transferable asset, that same dependency becomes a liability.

Where the Disconnect Begins

Owner income answers a personal question: How much am I taking home this year?

Sale value answers a different one: What would remain if I stepped away?

If most of the clinic’s profitability collapses without the owner present, buyers don’t view that income as durable. They see it as concentrated risk. This is why two owners earning similar amounts can receive very different outcomes when exploring a transaction.

A Common Comparison Buyers Make

| Clinic A | Clinic B |

|---|---|

| The owner produces a large share of revenue | Owner income comes partly from team output |

| High annual owner draw | Predictable margins across months |

| Limited associate autonomy | Clinical leadership distributed |

| Business performance is tightly linked to an individual | Systems absorb day‑to‑day disruptions |

Even if Clinic A pays its owner more today, Clinic B often commands more interest because its performance is repeatable. This distinction becomes especially visible during a formal veterinary practice evaluation, where buyer adjustments strip out income tied to personal effort rather than enterprise strength.

Why Owners Misread This Gap

The mistake is proximity. Owners live inside the business and feel the workload that produces their income. Buyers stand outside it and look for continuity.

That difference in perspective explains why owner income often needs to be reframed well before any sale discussion. Not reduced arbitrarily, but repositioned so it shows how the clinic performs as a system.

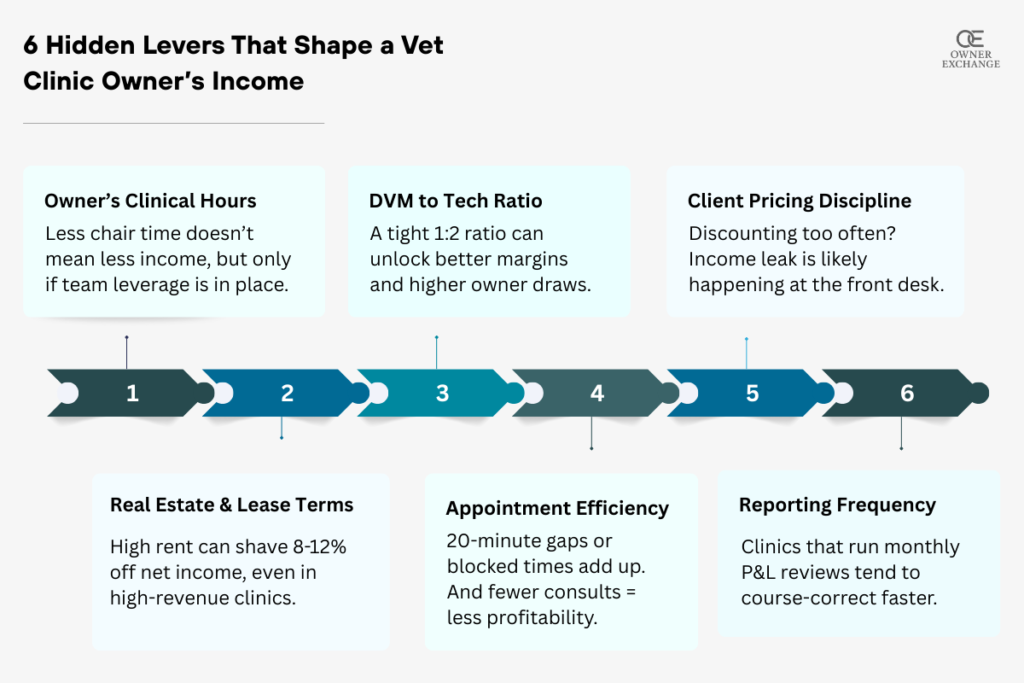

What Factors Drive a Vet Clinic Owner’s Take‑Home Pay?

Ask ten clinic owners how they decide their pay, and you’ll likely hear ten different answers. Some tie it to clinical production. Others pay themselves after every vendor, payroll, and subscription has cleared. A few follow accountant-driven rules, rarely adjusting based on actual clinic performance.

What’s missing in all three approaches is a framework. Because in veterinary businesses, the vet practice owner salary isn’t set; it’s defined.

3 Performance Layers That Influence Take-Home Pay

Instead of focusing only on topline production, owner income is better understood through these three layers:

1. Structural Leverage

Can the business generate revenue without you? If the answer is no, your income is tied to personal effort. Clinics with strong associate retention, efficient handovers, and reliable scheduling systems unlock more consistent pay and are more scalable.

2. Margin Control

Revenue growth without margin awareness rarely leads to more take-home income. Payroll creep, inventory waste, and fixed lease escalations eat into net profit silently. Owners who review margins monthly tend to catch the drift early and course-correct before it affects their income.

3. Role Transition

Owners who stay in the treatment room indefinitely often hit an earnings ceiling. As soon as time is spent hiring, training, solving conflicts, or managing growth, production drops, but income doesn’t adjust accordingly unless a transition plan is in place.

These variables explain why two owners with similar clinics take home vastly different incomes. It all comes down to the quality of infrastructure supporting that production.

How Ownership Structure Impacts Your Annual Earnings

Most clinic owners assume income rises automatically as the business grows. In practice, the structure of ownership decides how earnings are distributed, delayed, or restricted, often long before revenue becomes the issue.

A clinic can be profitable on paper and still feel tight at the owner level if the ownership framework doesn’t clearly separate compensation, profit access, and decision rights.

Common Ownership Structures & Income Behavior

| Ownership setup | How income typically flows | Where owners get caught |

|---|---|---|

| Sole owner, single entity | Draws taken after expenses | Income fluctuates wildly month to month |

| Sole owner with formal salary + distributions | Salary first, profits later | Requires discipline and forecasting |

| Multiple owners (equal shares) | Shared distributions | Conflicts when effort ≠ payout |

| Majority owner with minority buy‑ins | Split between pay + dividends | Poor agreements dilute income clarity |

| Post‑transaction retained equity | Reduced salary, future upside | Short‑term income drops surprise owners |

What’s important here is not which structure is “best,” but whether the structure matches the stage of the clinic. Problems arise when growth outpaces formalization.

Where Owners Lose Income Without Realizing It

- Informal draws that change month to month

- Partner expectations that were never documented

- Profit is retained unintentionally due to unclear distribution rules

- Compensation tied to habit instead of performance

These gaps become visible when owners start comparing themselves to peers, especially across different buyer types. In analyses of veterinary practice buyer demographics, income predictability consistently ranks higher than owner workload or personal production when practices are evaluated.

| Key Takeaway: If income depends on personal discretion, it rarely survives scrutiny. If income is embedded into structure, it becomes defensible and repeatable. |

Fixed Salary vs. Profit Draw: How Owners Actually Pay Themselves

How a clinic owner thinks they’re paying themselves and how they actually do it are often two very different things.

For some, income arrives through monthly draws pulled as needed. For others, it’s a formal W-2 salary issued on payroll. A third group relies on quarterly profit distribution, but only when cash flow allows it.

In reality, none of these is inherently wrong. But each method comes with trade-offs that affect taxes, predictability, and even how your clinic will be valued.

Two Income Streams Owners Generally Use:

| Method | Description | Owner Experience |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Salary | Regular payroll amount, often W-2 | Predictable, tax-reported income; easier to budget |

| Profit Draw | Non-salaried withdrawals from net profit | Irregular, varies by month; can distort performance if undisciplined |

Fixed Salary: Clean, But Not Always Complete

When owners set up payroll for themselves, they usually aim for structure. Regular deposits, tax withholdings, and visible compensation on financial reports.

But here’s the catch: many underpay themselves, leaving “profit” behind in the business with the intention of taking it out later. That works until it doesn’t. Buyers may see this underpayment as inflated profit, and adjust EBITDA down once a realistic salary is factored in.

Profit Draws: Flexible, But Often Fuzzy

Owners who rely on draws tend to pay themselves reactively. If the month was good, they take more. If margins were tight, they would wait. While this can be fine during early ownership years, it causes problems when:

- The owner can’t clearly state their annual income

- Business health appears stronger than it is (because salary is invisible)

- Profit is reinvested inconsistently, making trends impossible to track

Draws also raise tax strategy questions. Without documentation, they blur into personal withdrawals and complicate year-end accounting, particularly when exploring veterinary practice transition services, where clean, auditable income is non-negotiable.

Are Veterinary Practices Still Profitable in a Changing Market?

Yes, vet clinics are still profitable. But the definition of what makes them profitable has changed.

Owners who made high income a few years ago, doing things the same way this year, are often earning less, working more, and are unsure where the money’s going. That’s not because the market has collapsed. It’s because margin discipline matters more than volume now.

Let’s Compare: Yesterday’s Profit vs. Today’s Reality

| Factor | Then (pre-2020) | Now |

|---|---|---|

| Revenue growth | Predictable year over year | Variable with staff shortages and burnout |

| Payroll cost | 35-40% of revenue | 42-55% (and still rising) |

| Inventory spend | Easy to control | Creeping up due to supplier lock-ins and inflation |

| Real estate | Mostly fixed | Rising lease escalators, limited space flexibility |

| Tech costs | Minimal | Subscriptions are eating 2-4% of topline if unmonitored |

What this means for a vet practice owner salary is straightforward: If you’re not reviewing margins every month, profitability erodes quietly.

Where Profit Still Lives (but Owners Often Overlook It)

- Scheduling optimization: Shifting from “full days” to strategically built appointments improves DVM output without increasing hours.

- Inventory streamlining: Every vet knows what a bottle of meds costs. Fewer track expiry waste and markup consistency across SKUs.

- Payroll audits: Too many clinics are overstaffed during slow days, understaffed during peaks, bleeding margin from both ends.

- Client pricing tolerance: Undercharging remains one of the most widespread causes of lost profitability. Most clients don’t leave over $10-$20 increases, but most owners assume they will.

Owners who run these reviews quarterly (or better, monthly) consistently report stronger margins even if revenue hasn’t grown. That’s why retirement planning for veterinary practice owners now starts with cash flow visibility.

When Owner Salary Drops: Common Financial Red Flags

When owners notice their salary slipping, the first reaction is often self-blame. Work harder. Produce more. Stay later. But income decline is more often a diagnostic signal than a performance issue.

The challenge is learning to read that signal correctly.

Patterns That Precede a Pay Drop

- Pattern 1: Margin compression goes unnoticed. Small increases in payroll, inventory, or tech stack costs rarely trigger alarms individually. Together, they reduce distributable income month after month.

- Pattern 2: Compensation decisions lag reality. Owners keep the same pay structure despite higher complexity. What worked at $1M revenue breaks at $2.5M but salary logic stays unchanged.

- Pattern 3: Growth without delegation. More associates don’t always mean less owner workload. Without authority transfer, the owner becomes the bottleneck, earning less while managing more.

What Buyers Read Between the Lines

Declining owner income isn’t automatically a red flag for buyers. Unexplained decline is.

During early diligence, buyers often ask:

- Is the drop intentional or reactive?

- Does income rebound when the owner steps back in?

- Is compensation tied to performance or convenience?

These questions come up early for anyone exploring options around who is buying veterinary practices, because income volatility directly affects perceived risk even before financial statements are normalized.

How Owners Should Respond

A falling salary isn’t always a warning to exit. Often, it’s an invitation to reassess:

- Cost structure vs revenue mix

- Owner role vs team capability

- Pay design vs growth stage

Owners who address these early tend to recover income without increasing hours and place themselves in a stronger position if they later choose to transition.

How Tax Strategy Affects Reported Vet Practice Owner Income

Tax planning in veterinary ownership is often reactive:

“Take less now, save on taxes.”

“Let profit sit in the business until year-end.”

“Draw what you need, and leave the rest.”

These strategies may work short-term but they can distort what the clinic actually earns and what the owner actually makes.

3 Ways Tax Strategy Skews Income Perception

- Underpaying on purpose: Some owners pay themselves a below-market salary to keep payroll tax low. While this reduces short-term liability, it hides the clinic’s true labor cost and weakens EBITDA accuracy.

- Leaving profits “in the business”: Undrawn profits aren’t taxed until withdrawn in many structures. But to a buyer, these profits still count, especially if they’ve supported operations or vendor pay during tight months.

- Blurring business and personal: Owners who run discretionary expenses through the business (vehicles, travel, etc.) often understate net income. It might lower taxes, but it muddies the clinic’s performance story.

Why This is Important for Vet Owner Salary

| Tax Behavior | Outcome on Salary |

|---|---|

| Salary reduced to avoid payroll tax | Lower reported income, higher buyer adjustment |

| Profits drawn inconsistently | Unclear compensation trends |

| Personal expenses written off | Red flags during diligence even if legal |

This is why many advisors recommend separating tax strategy from financial narrative at least two years before any potential transition.

Do Multi-Location Owners Make Significantly More?

The assumption is common: more clinics = more income. But in practice, multi-location ownership introduces complexity that doesn’t always translate into better take-home pay.

In fact, many multi-site owners report lower per-clinic income than they earned as solo operators, especially in the first few years after expanding.

Comparing Income Profiles: Single vs. Multi-Location

| Setup | Common Revenue | Typical Challenges | Owner Pay Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-location clinic | $1.2M – $2.5M | Owner-dependent, margin fluctuation | Income tied to personal production |

| Multi-location (2-3 sites) | $3.5M – $8M+ | Staffing, delegation, margin control | Owner salary flattens or drops due to reinvestment |

| Group practice (>5 locations) | $10M+ | Executive role replaces clinical | Salary returns stronger only if systems are stable |

What Owners Learn After Expanding

- Staffing becomes the bottleneck, not clients

- Margins compress, especially during onboarding and integration

- Personal income dips, often for 18-36 months post-acquisition

And yet for well-structured businesses, long-term upside is real. Owner salary increases not from volume, but from leverage. When non-clinical roles are hired (COO, marketing lead, practice manager layer), profitability begins to decouple from hours worked.

This trend shows up clearly in analysis of corporate veterinary ownership models, where owners who retain equity in a structured group often earn less upfront but capture more wealth via strategic payout or future sale.

How Much Can You Make Owning a Vet Clinic With No Clinical Role?

For many clinic owners, the idea of earning without doing clinical work feels either aspirational or unrealistic. But it’s possible. The real question isn’t if you can earn a healthy vet practice owner salary without being on the floor. It’s how.

Owners who succeed in this shift have one thing in common: They stop thinking like a clinician and start operating like a system designer.

What Changes When You Stop Producing Cases

| Category | While Producing | After Stepping Back |

|---|---|---|

| Income source | Personal caseload + margin | Margin only (must be stable) |

| Team management | Hands-on, daily involvement | Delegated through lead DVM or manager |

| Profit access | More flexible, tied to schedule | More structured, tied to reporting cycles |

| Buyer appeal | May be owner-dependent | Considered more transferable |

The transition replaces production-based income with leadership-based return but only if the practice is set up to function without daily supervision.

How Owners Successfully Shift Away From Clinical Work

- Build an associate team with aligned production incentives. Without high-output DVMs in place, stepping back just means lost revenue.

- Document operational decisions. If processes only live in your head, delegation will fail and income will suffer.

- Install reporting that flags problems early. Margin slippage is harder to catch when you’re not seeing patients. Build visibility into systems.

This structure is what buyers like Southern Veterinary Partners specifically look for when assessing multi-location groups or owner-light clinics: scalable profit, clean reporting, and low dependency on any one person.

What is the Realistic Pay Range for a 1-Doctor vs. 5-Doctor Practice?

Most assume this: “If I grow from 1 vet to 5 vets, I’ll go from $200K/year to $500K/year.”

But here’s what the numbers don’t show: most 5-DVM clinics still pay their owner less than $350K. And in many cases, it’s not much higher than what a solo DVM makes with a lean team and stable caseload.

Let’s compare in format that reveals the hidden inefficiencies:

| Practice Type | Clinical Load | Staff Complexity | Admin Time | Owner Pay Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-DVM Practice | 90% hands-on | Low (5-6 total) | Minimal | $180K – $250K |

| 5-DVM Practice | 0-20% | High (20-30+) | 10-20 hrs/week | $250K – $350K |

Hidden Factors That Impact Salary (Not Just Revenue)

- Owner involvement: The less the practice runs without you, the harder it is to increase pay. Owner-dependent practices plateau fast.

- Leadership layering: Many 5-DVM clinics lack department leads or true delegation, forcing the owner back into every operational hole.

- Margin compression: Hiring more doesn’t guarantee profit. Payroll grows faster than revenue in multi-vet clinics, especially without pricing alignment.

These patterns come up consistently in operational red flag reviews done before a sale. Owners realize they’ve scaled patient volume, not profitability and the gap between gross and take-home widens.

| Key Takeaway: A 1-vet owner who’s clinically efficient, prices smartly, and keeps ops tight can clear $230K+ a year with far less risk. A 5-vet clinic with leaky margins and unclear leadership? Often stuck under $300K despite looking “larger.” |

Common Misconceptions About Multi-DVM Income

⛔ “More vets = automatic pay bump.” Most of the added income gets redistributed into salaries, benefits, admin time, and overhead, especially if pricing isn’t adjusted along the way.

⛔ “I’ll just hire an office manager.” True leadership requires process architecture, not task delegation. Otherwise, you stay in every bottleneck and spend your weekends fixing chaos.

Link between structure and salary is what makes buyers place such high value on clinics that run lean and clean. It’s why firms like VMG often benchmark 2-DVM clinics as better earners than sprawling, bloated groups.

Should You Reduce Your Salary Before Selling Your Practice?

Reducing your owner salary to inflate EBITDA might seem like a smart valuation play. But without context, it often signals risk.

Buyers, especially private equity firms or consolidators, aren’t just looking at numbers. They’re evaluating sustainability. And if your salary appears artificially suppressed, it raises two questions:

- Who’s doing the work today?

- Who’ll take over those responsibilities post-sale?

If your clinical, managerial, or strategic input is still critical to the business and your W2 or owner draw has dipped, they know a replacement cost is coming.

Why Artificially Lowering Salary Can Backfire

| Red Flag | Buyer Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Salary slashed with no labor shift | “They’re inflating margins.” |

| No record of substitute hires | “Owner still carries the workload.” |

| No explanation in seller’s narrative | “Risk of post-close burnout or misalignment.” |

When (and How) a Reduced Salary Does Make Sense

- If you’ve hired associates to take over your caseload and your time commitment genuinely dropped

- If you’re transitioning out of ops and can show a support team or practice manager in place

- If your profit growth outpaces the salary dip (i.e., you didn’t slash pay to manufacture margin)

These conditions must be documented clearly in your practice profile, ideally with a 12-18 month runway. That gives the buyer visibility into a stable earnings base that isn’t dependent on underpaid owner labor.

Tip: Instead of cutting salary close to the sale date, redirect income strategically:

- Bonus out key team members (retention)

- Invest in marketing or technology (growth)

- Add systems that reduce owner workload (reduces dependency)

How Exit Timing Affects What You Actually Take Home

The timing of your exit doesn’t just influence valuation, it changes your actual take-home. Many $2M+ practice owners focus on the sale price, but ignore what eats into it:

- Earn-outs tied to post-sale metrics

- Tax treatment based on structure + timing

- Retention bonuses for team continuity

- Market cycles shifting buyer leverage

A “high multiple” in the wrong month can still net you less than a strategic exit aligned with tax planning, buyer funding windows, or seasonal trends.

Timing Traps That Dent Payouts

| Exit Scenario | What Happens | Real Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Sale closes before tax year planning | Unoptimized structure | 15-20% more in taxes |

| Exit during market correction | Fewer buyers, tighter terms | More earn-out, less cash |

| Sold before second doctor stabilizes | Buyer flags dependency risk | Valuation discount |

| Exit rushed before Q4 metrics | No time to lock in margin gains | Lower trailing EBITDA |

What to Lock In Before Listing Your Clinic for Sale

- Sustainable earnings base (past 12-18 months)

- A clear transition plan for your role

- Documented associate retention strategy

- Latest Q4 results baked into TTM EBITDA

Once those align, your exit terms can shift from “buyer-controlled” to “seller-leveraged.”

| Tip: You can time your exit around peak trailing margins. Even a 5% margin lift before listing can shift your pricing and deal terms. For related prep advice, explore operational red flags that lower valuation. |

Conclusion

How much you pay yourself only becomes a problem when it doesn’t make sense on paper.

If your salary is too low, buyers assume hidden risk.

If it’s too high, they assume the business can’t run without you.

If it changes suddenly, they assume the numbers were adjusted for a sale.

A realistic vet practice owner salary isn’t about optimization or optics. It’s about showing that the clinic can support a fair owner role, year after year, without stretching the math. When that’s clear, everything else in the deal becomes easier: pricing, structure, and what you actually walk away with.

FAQs: Vet Practice Owner Salary

1. Should I match my salary to associate benchmarks before selling?

That’s one approach, but not always the best. Many buyers prefer a defensible salary aligned with replacement cost. If you’re the lead producer, underpaying yourself to boost EBITDA will only raise red flags later.

2. How do buyers view bonus structures or profit-sharing payouts?

Discretionary bonuses are often added back if clearly tracked. But if they’re inconsistent or undocumented, buyers might treat them as part of base comp, cutting into valuation.

3. Can adjusting my salary too close to sale time backfire?

Yes. Sudden changes raise questions. If you need to rebalance salary and distributions, start at least 12-18 months ahead so there’s a track record that buyers can trust.

Melani Seymour, co-founder of Transitions Elite, helps veterinary practice owners take action now to maximize value and secure their future.

With over 15 years of experience guiding thousands of owners, she knows exactly what it takes to achieve the best outcome.

Ready to see what your practice is worth?